Last week, we got to represent the Texas Digital Newspaper Program at the Texas Press Association’s 2023 Annual Meeting & Trade Show. Tim Gieringer and Ana Krahmer ran a vendor table, which gave them the chance to speak with publishers from across Texas about community news preservation. The Texas Press Association partners with UNT Libraries to digitally preserve their member-publisher PDF editions, which are submitted to TPA for clipping service and then compiled by UNT for digital preservation; with publisher permission, UNT also makes these PDF editions publicly available via The Portal to Texas History. Texas is a leader in the U.S. in born-digital PDF preservation because of this partnership, and this is one of the many reasons we love visiting with publishers to talk about preserving and building digital access to their newspaper runs. Our participation in the Texas Press Association was sponsored by the Cathy N. Hartman Portal to Texas History Endowment.

Texas has a very long publishing history, with news related to the area spanning from when it was still part of Spain, and Texas publishers truly recognize the importance of capturing this history. While the Texas Digital Newspaper Program can midwife digitization of a community’s newspaper run at all stages, from physical newspaper pages to a digitally-preserved, open collection, the publishers are the people on the front lines, and they have been preserving the physical newspapers for decades. The work of TDNP is only possible through the support of and appreciation for history that our Texas publishers show, and the Texas Press Association annual meetings teach us this every year.

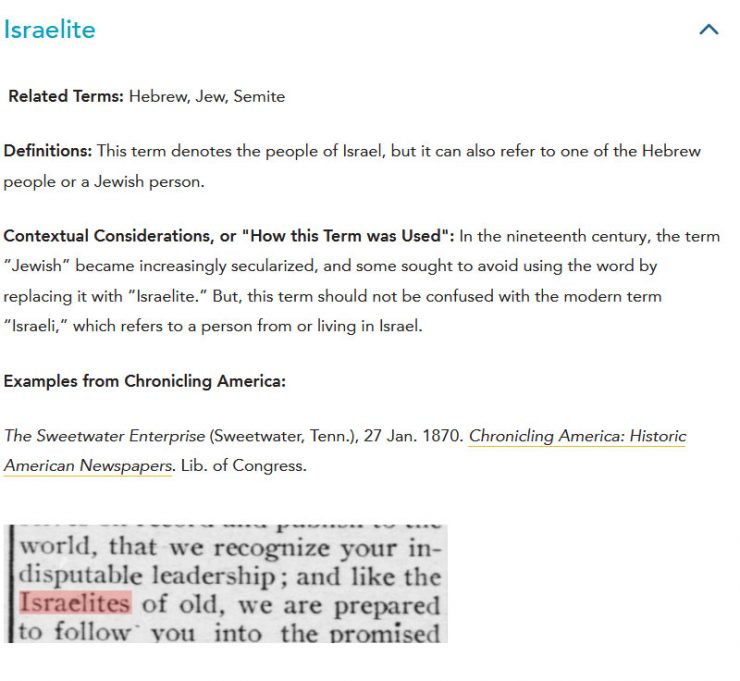

At these annual meetings, we talk with three different types of publishers:

Ana Krahmer and Tim Gieringer hosted a vendor table at the 2023 Texas Press Association Annual meeting, on June 1-2.

1) people who are working with us already; 2) people who have heard of us but aren’t sure how to participate; 3) people who have not heard of us. We think of the group 1 publishers as the veterans, some of whom have been partners with TDNP for over a decade. With this group, we talk about new ways to use The Portal to Texas History for research, and we always like to continue the conversation about local preservation with libraries or historical societies in their cities. We walk the second group through our work processes, including how to coordinate with their local libraries to apply for grant funding, explaining the different groups who support digital newspaper preservation in Texas:

- The Tocker Foundation: Supports newspaper digitization projects for Texas communities with populations below 12,000.

- The Ladd & Katherine Hancher Library Foundation: Supports newspaper digitization for Texas communities with populations below 50,000.

- The Texas State Library & Archives Commission: Funded through the Institution of Museum and Library Services’ Library Services and Technology Act, the TexTreasures grants are a competitive program administered by the Texas State Library & Archives Commission, supporting newspaper digitization for libraries across the state, representing communities of any population size.

When we meet with the third group, we get to show off the newspaper collection on The Portal to Texas History, explaining that TDNP is the largest, single-state, open-access digital preservation repository for newspapers in the U.S. We also introduce these publishers to Chronicling America, which provides access to newspapers from all fifty states. Our goal is to help show publishers the value of building a digital preservation archive for their newspaper collections, in hopes that they will one day be interested in partnering with us to add their content.

Newspaper publishers do a lot of invisible work for their communities, and one of the most valuable and important things they do is preserving their newspaper collections. We are both honored and overjoyed to help publishers with their preservation efforts, and we thank the Texas Press Association for their continued dedication to helping publishers in this endeavor.

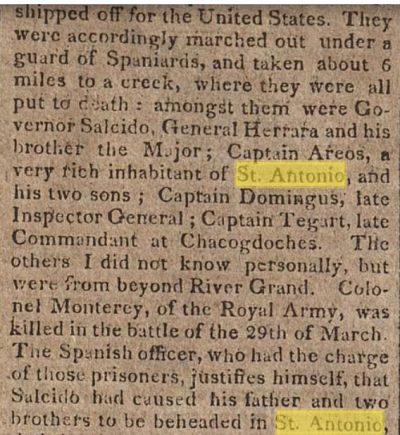

Searching for “St. Antonio” on the Portal locates 1813 issues of the National Intelligencer, documenting the Mexican revolt from Spanish authority, such as

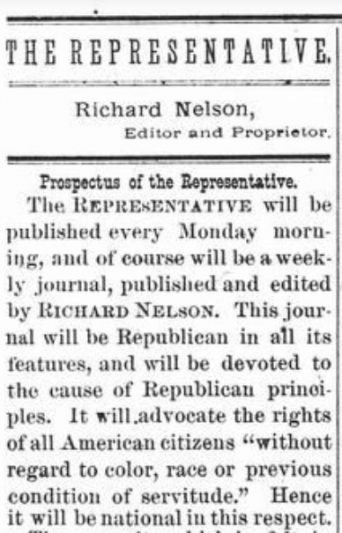

Searching for “St. Antonio” on the Portal locates 1813 issues of the National Intelligencer, documenting the Mexican revolt from Spanish authority, such as This clipping from volume 1, number 1, highlights the mission of the first African American-owned and edited newspaper in Texas. Published by Richard Nelson,

This clipping from volume 1, number 1, highlights the mission of the first African American-owned and edited newspaper in Texas. Published by Richard Nelson, Weatherbird: I’m happy because I’m alive,

Weatherbird: I’m happy because I’m alive, Weatherbird: It’s anything for style,

Weatherbird: It’s anything for style, Weatherbird, asking the sun to “have a heart!” in

Weatherbird, asking the sun to “have a heart!” in Weatherbird encourages suffrage, but it will be windy, according to

Weatherbird encourages suffrage, but it will be windy, according to