The University of North Texas Libraries is proud to announce the six awardees of The Portal to Texas History Research Fellowship for 2018: Kimberly Jackson, Scot McFarlane, Shay O’Brien, Richard B. McCaslin, Kenna Lang Archer and Jessica Webb.

Research using the Portal is relevant to studies in a variety of disciplines including history, journalism, political science, geography, and American studies. These awardees all thought of creative opportunities that research with the large digital library collection can enable.

The following are the short project descriptions from each awardee. The biographical information for our 2018 awardees can be found at the UNT Libraries’ Research Fellowships page.

Kimberly Jackson

Project Title: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Big Bend National Park

“My project is a case study of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Big Bend National Park. If it were not for the work of the CCC in Big Bend, the national park would not exist as we know it today. There does not currently exist a study on the CCC in Big Bend, and as such my research will help us to better understand the overall history and development of Big Bend.”

Richard B. McCaslin

Project Title: Pompeo Coppini: Defining the Historical Landscape in Texas

“Pompeo Coppini, a classically trained sculptor from Italy, arrived in Texas at the onset of the Progressive Era, with its emphasis on such initiatives as the City Beautiful movement and historical tourism. Beginning in 1902, Coppini during more than five decades created dozens of iconic works in Texas focusing first on the Lost Cause, then the heritage of the Republic of Texas and the contributions of many local leaders. While his historical works also stand in many other states and several foreign countries, his greatest impact was in defining the historical landscape of Texas, or the imagery that shapes public perceptions of the past in the Lone Star State.”

Scot McFarlane

Project Title: The City and the Countryside on Texas’ Trinity River

“This project uses the history of the Trinity River to explore Texas’s ongoing transition from a rural to an urban state. While the pollution from North Texas always flowed down the Trinity into East Texas, politics and patronage meant both regions depended on each other. Furthermore, the power of the flooding Trinity River helped people resist the elite’s attempts to control their lives from within and beyond East Texas.”

Kenna Lang Archer

Project Title: Keeping Cool in Texas: A History

“The State of Texas is known for its highly variable weather and for the extraordinary heat that periodically roasts crops, accosts livestock, and challenges public morale. Keeping cool in this state has become both science and art, but efforts to beat the heat are nothing new. This project studies the long history of keeping cool in Texas from a social, environmental, and cultural perspective, paying special attention to the shifting relationship between technological dependence and climatological adaptation.”

Jessica Webb

Project Title: Prostitution and Power in Progressive-Era Texas: Entrepreneurship and the Influence of Madams in Fort Worth and San Antonio, 1877-1920

“‘Prostitution and Power’ examines the lives and careers of the women who owned and managed houses of prostitution, known as madams, in the red-light districts of Fort Worth and San Antonio. Moving from the latter decades of the nineteenth century up to the First World War, this project charts the expansion of prostitution, and the ability of these madams to obtain a substantial amount of social, political, and economic power, and the decline—of both the sex trade and its madams.”

Shay O’Brien

Project Title: Mapping Elite Social Networks in Dallas, 1896-1956

“Using social registers supplemented by the Portal to Texas History and other archival sources, I am building a comprehensive longitudinal dataset of members of Dallas high society from 1896-1956. I am compiling information on each person’s basic biographical data, family relationships, close friendships, home addresses, and organizational memberships, such as churches and synagogues, workplaces, schools, and social clubs. When the dataset is complete, I will use it as the basis of numerous studies, beginning with one on the impact of the 1930 oil boom on the centers of Dallas sociopolitical power.”

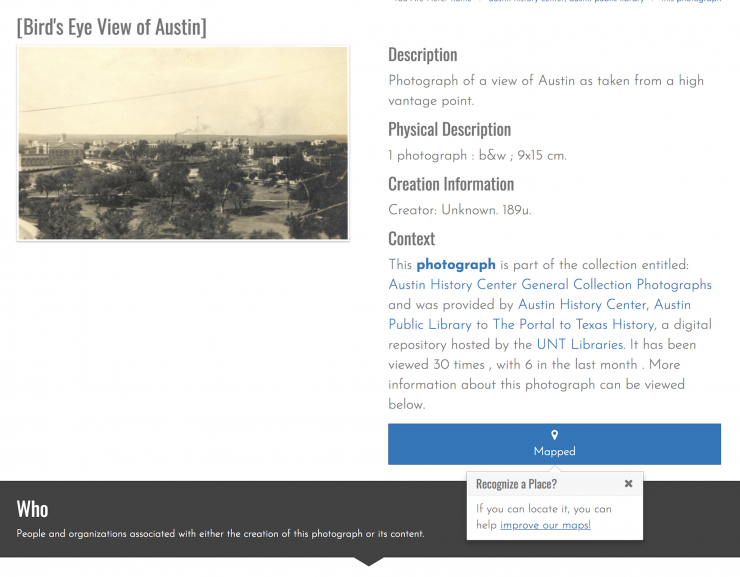

Figure 2. Screenshot of Portal. Popover visible in lower-right corner.

Figure 2. Screenshot of Portal. Popover visible in lower-right corner. Figure 3. Search Results. One item has coordinates.

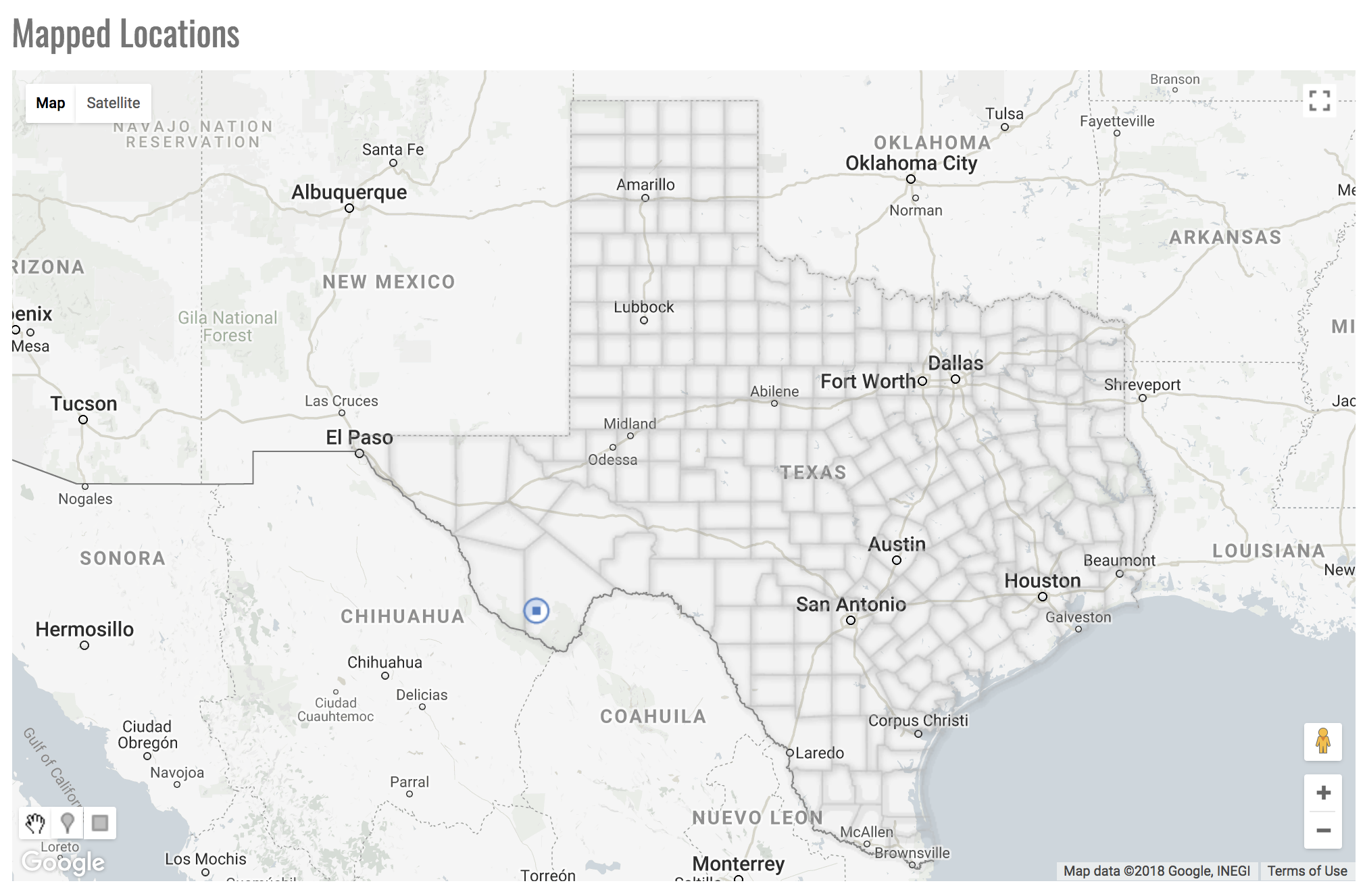

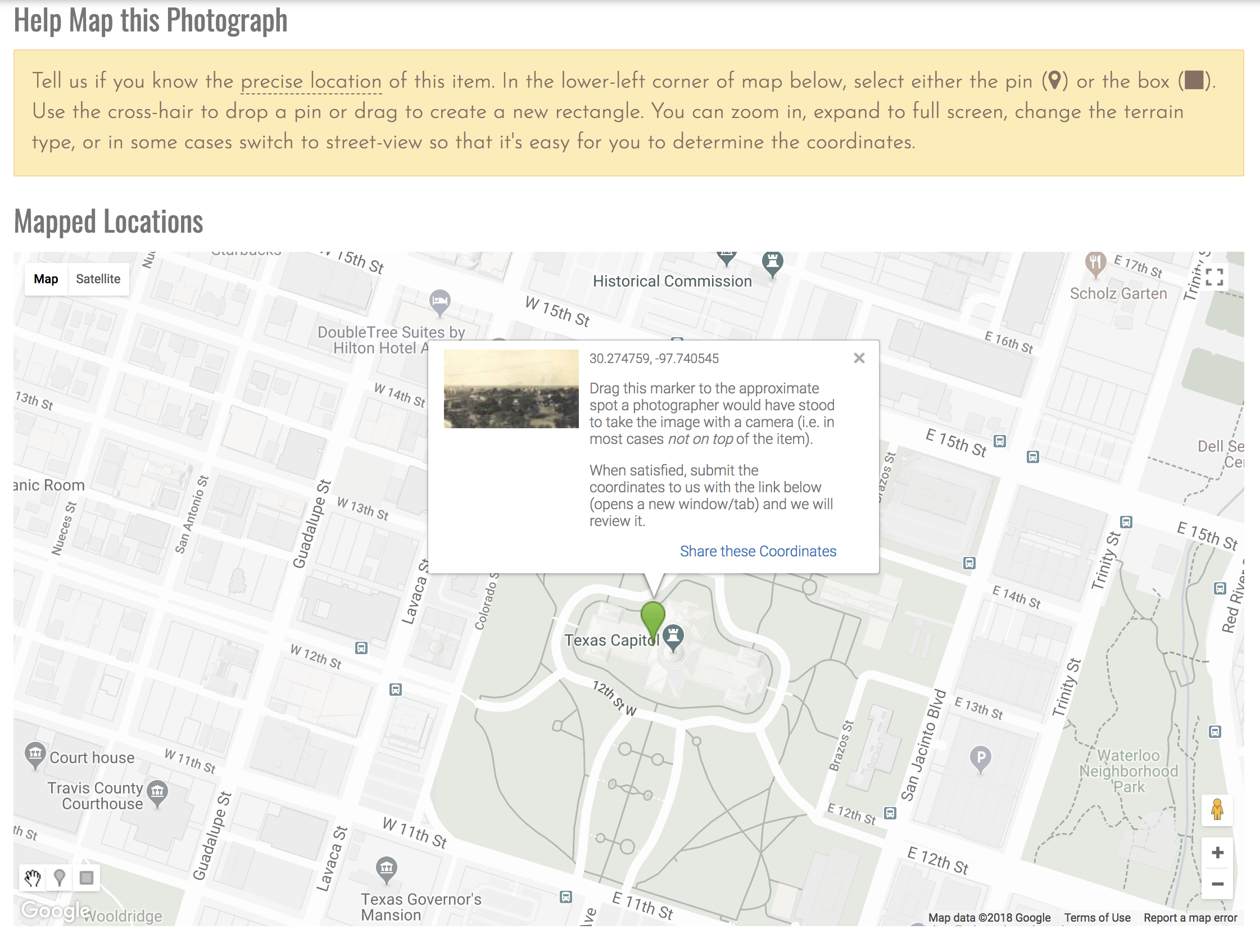

Figure 3. Search Results. One item has coordinates. Figure 4. View of new mapping tool with place point marker set.

Figure 4. View of new mapping tool with place point marker set.

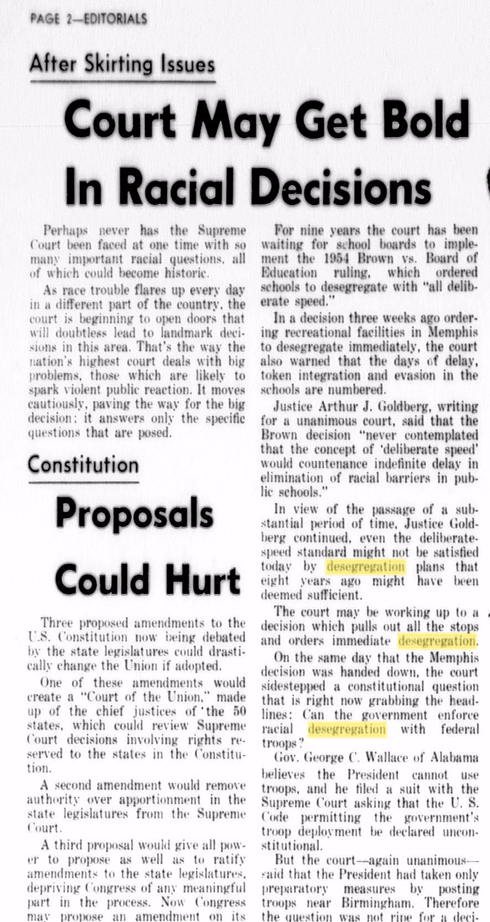

I also wrote interpretive essays about how members of the Fellowship contributed to the history of Denton. Aside from using past and present oral interviews for my biographical sketches and essays, I incorporated Texas Digital Newspaper Program titles, particularly

I also wrote interpretive essays about how members of the Fellowship contributed to the history of Denton. Aside from using past and present oral interviews for my biographical sketches and essays, I incorporated Texas Digital Newspaper Program titles, particularly